Value Creation is Not Symmetric : Life, Relationships, and Organizations

Humans are inherently driven to seek value, create meaning, and leave a lasting impact. This urge to create value is deeply embedded in our psychology, touching on our need for survival, social connection, identity, purpose, and legacy. Value creation — the process of generating meaningful outcomes, benefits, or impact — is often idealized as a balanced, mutual exchange in different spheres of life. In theory, value creation might seem like a linear, reciprocal transaction: if you invest effort, you receive proportionate returns. However, the reality is far from symmetric. Value creation in life, relationships, and organizations operates in complex, often imbalanced, dynamics. This asymmetry arises due to differences in perspectives, expectations, power structures, and resource distribution. Let’s dive in further.

But before we try to explore the nature of asymmetry in value creation across three domains: life, relationships, and organizations, focusing on how these imbalances shape outcomes and what we can learn from them; let’s explore the psychological motivations that drive humanity’s quest for value creation.

1. Value as a Survival Mechanism (Survival and Evolutionary Psychology)

At the most basic level, the drive to create value stems from our evolutionary roots. In evolutionary psychology, value creation is tied to the fundamental human need to survive and reproduce. Our ancestors, driven by the necessity to secure resources and protection, developed behaviors that increased their chances of survival. In this sense, value creation—whether through skills, social cooperation, or innovation—was key to ensuring not just individual survival but the survival of the group.

Humans are inherently social creatures, and early humans learned that cooperation was a critical element in survival. By creating value for the group (e.g., through hunting, sharing resources, or protection), individuals enhanced their status within the group and ensured reciprocal support. This led to the development of prosocial behaviors — actions that benefit others and the community — which are still deeply ingrained in modern human psychology. The need to create value within a community has been reinforced by social reciprocity and mutual aid. People who contributed to the welfare of others often received support in return, creating a positive feedback loop that bolstered group cohesion and individual standing.

2. The Need for Purpose and Meaning (Existential Psychology)

On a more profound psychological level, value creation is closely tied to the human need for purpose and meaning. Existential psychology posits that humans are meaning-seeking creatures. In a world that can often feel chaotic or purposeless, creating value gives individuals a sense of order, control, and significance. Existential thinkers like Viktor Frankl and Ernest Becker argued that humans are driven to find meaning as a way to cope with the inherent anxieties of existence, particularly the knowledge of death. Frankl noted that humans can endure almost any suffering as long as they believe their lives have meaning. Value creation is one way we define that meaning—whether it’s contributing to society, raising a family, or excelling in a profession, people seek to leave a mark that affirms their life mattered. In contrast to nihilism, which asserts that life lacks inherent meaning, value creation allows individuals to combat feelings of futility. By investing in activities or projects that yield tangible results, people construct a narrative of significance. Even in a world where cosmic meaning may be elusive, humans create localized meaning through the value they bring to themselves, others, or society. This search for meaning is often personal and subjective, driven by individual values and cultural influences.

3. Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness (Self-Determination Theory)

Self-determination theory (SDT), developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, identifies three core psychological needs that motivate human behavior: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Value creation plays a crucial role in satisfying these needs.

Autonomy : Autonomy refers to the need to feel that one’s actions are self-directed and aligned with personal values. Creating value allows individuals to assert their independence and shape their environment. Whether through artistic expression, entrepreneurship, or personal projects, value creation gives people a sense of control over their lives, reinforcing their autonomy.

Competence : The need for competence is the desire to feel capable and effective in one’s actions. Value creation is deeply tied to this need — when people see the results of their efforts, it reinforces their sense of mastery. Completing a project, excelling at a task, or helping others in meaningful ways affirms one’s skills and abilities, fulfilling the need for competence.

Relatedness : Finally, relatedness refers to the need for social connection and belonging. People seek value creation as a way to connect with others and contribute to something larger than themselves. Whether in relationships, communities, or workplaces, value creation fosters a sense of belonging and reinforces social bonds, as people feel they are part of a collective endeavor.

4. Value as a Measure of Worth (Status and Social Identity)

Another powerful psychological drive behind value creation is the need for status and social identity. Humans are inherently hierarchical creatures, and value creation often determines one’s standing within a group or society. By contributing to society — through work, innovation, leadership, or social influence—people enhance their status and gain recognition, reinforcing their sense of self-worth.

The Drive for Recognition : People often seek external validation for their efforts. Whether through professional success, social achievements, or intellectual contributions, value creation is a way to gain recognition from others. This recognition feeds into self-esteem, affirming that one’s efforts are seen, valued, and respected by others. In this sense, value creation becomes a measure of personal worth in the eyes of society.

Social Identity Theory : Social identity theory, proposed by psychologist Henri Tajfel, suggests that people derive a sense of identity from the groups they belong to. Value creation within a group, whether it’s a workplace, community, or social movement, reinforces one’s identity and solidifies their role within that group. By contributing value, individuals affirm their place in a social hierarchy, which helps shape how they see themselves and how others see them.

5. Value Creation as Immortality (The Legacy Drive)

Psychologist Ernest Becker argued that much of human behavior is motivated by the fear of death, and that value creation is often an attempt to achieve symbolic immortality. By leaving behind something meaningful — a piece of art, a company, a scientific breakthrough, or even a family — people transcend their mortality.

The Denial of Death : In Becker’s book The Denial of Death, he posits that humans are driven to create value in part to defy their inevitable end. This is seen in efforts to build legacies, whether through professional accomplishments, creative endeavors, or the nurturing of future generations. Value creation offers a psychological buffer against the fear of impermanence by allowing individuals to leave something lasting after they are gone.

Creating a Legacy : For many, creating value is synonymous with building a legacy. People want to be remembered for the impact they had on the world. This drive to create value for future generations can be seen in philanthropy, entrepreneurship, scientific discovery, and parenthood. By contributing something meaningful, individuals feel they are part of something larger than themselves, achieving a kind of symbolic immortality.

Now let’s dive into the Asymmetrical nature of value creation.

1. Asymmetry in Life : The Complex Dynamics of Effort and Outcome

In life, many believe in a direct correlation between effort and reward, but the relationship is anything but linear. Rather, it often mirrors non-linear systems, where similar inputs can result in wildly different outcomes due to factors like privilege, randomness, or timing. Life can be viewed as a chaotic system, one that operates under sensitive dependence on initial conditions — a hallmark of chaos theory. Small differences in initial conditions (such as wealth, education, or opportunity) lead to vastly different results, resembling the famous “butterfly effect.”

Non-Linear Growth : Compounding vs. Diminishing Returns

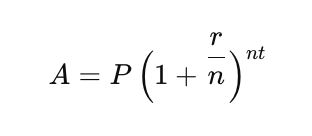

In mathematical terms, life’s rewards follow an exponential, rather than a linear, growth model. For individuals starting with advantageous conditions, such as wealth or education, the rewards compound. This phenomenon can be represented by the equation for compound interest:

Here, P represents initial resources, and r the rate of opportunity and effort applied. Those with better starting points see their efforts multiply, creating an exponential disparity in value creation compared to those with fewer initial resources.

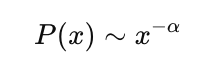

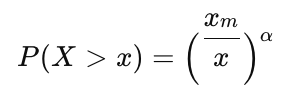

Conversely, individuals without privileged starts may experience diminishing returns, where additional effort yields progressively smaller rewards. This disparity is further exacerbated by randomness—a key feature in probability distributions — which governs life’s unpredictability. Some outcomes are shaped by chance events, leading to extreme outliers where a few capture the majority of wealth and success, as modeled by power-law distributions:

This probabilistic nature explains why a small number of individuals (e.g., billionaires or influential leaders) control most of the world’s wealth, while the vast majority capture only a fraction of that value.

Luck and the Power of Randomness

Life’s randomness is not merely incidental; it is central to understanding asymmetry. Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s concept of Black Swan events highlights that rare, unpredictable occurrences have a disproportionate impact on outcomes. Despite equal effort and talent, two individuals may experience dramatically different results because of luck, timing, or unforeseen circumstances. As a result, life’s value creation operates in a probabilistic landscape, governed as much by randomness as by intention.

Philosophically, this resonates with the existential idea that life is not inherently fair. As Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre have noted, human existence is marked by absurdity, where outcomes often seem unrelated to the actions that precede them. Success, then, is less about deserving and more about being positioned at the intersection of effort and opportunity — an intersection not everyone will encounter.

In short :

- In life, the idea that hard work and talent inevitably lead to success is a popular narrative. While personal agency plays a role, there are external factors — social background, opportunity, privilege, randomness — that cause asymmetry in value creation.

- Life is filled with unpredictable, high-impact occurrences. Even when two individuals exhibit the same level of effort, education, and talent, their outcomes can be drastically different due to chance or circumstantial factors.

- The disparity in value creation is driven by the inequities in starting conditions. This dynamic is most visibly represented in studies of wealth inequality, where wealth begets more wealth due to compounding interest and investment opportunities, while those with fewer resources struggle to create the same levels of value.

- People may invest years of their lives into mastering a skill, yet may never receive recognition for their work. This is not necessarily due to a lack of value in their contributions, but because attention, fame, and recognition are resources distributed unevenly across society. Visibility is not correlated with quality or effort—creating a lopsided value creation process where certain individuals or groups disproportionately capture the rewards.

2. Asymmetry in Relationships : Emotional Labor, Power, and Game Theory

Human relationships are an intricate web of emotional, psychological, and social investments, yet these investments are rarely equal between two people. Asymmetric value creation in relationships often manifests in terms of emotional labor, power dynamics, and the unequal exchange of resources. Using mathematical models like game theory and network theory, we can analyze these imbalances and their effects on relational dynamics.

Game Theory : Imbalances in Emotional Labor

In relationships, especially romantic or familial ones, emotional labor—defined as the invisible work involved in managing emotions and resolving conflicts — is often distributed asymmetrically. One partner may invest more emotional effort, leading to an unequal exchange of value. This dynamic resembles a non-cooperative game in game theory, where one partner invests more (cooperates), while the other contributes less (defects), capturing a disproportionate amount of the relationship’s benefits.

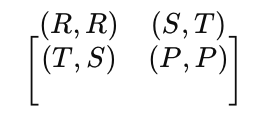

This is modeled in a payoff matrix similar to the prisoner’s dilemma:

Where C represents cooperation (emotional investment) and D represents defection (reduced investment). The partner who defects typically gains more value at the cost of the cooperating partner, illustrating how emotional labor is often undervalued and disproportionately burdens one side of the relationship.

Power Dynamics : Nash Equilibrium and Bargaining Power

In relationships where power dynamics are at play, such as mentor-mentee or hierarchical relationships, the Nash equilibrium helps explain why value creation is often asymmetric. The individual with more social, emotional, or financial power dictates the terms of the relationship, leading to an unequal payoff structure. Even in non-romantic relationships, this imbalance creates a situation where the powerful party captures more value while contributing relatively less.

Network Theory : Centrality and Social Influence

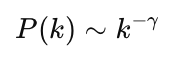

The asymmetry of value in relationships is also influenced by one’s centrality in social networks. In network theory, individuals with more social connections or influence (hubs) have access to more resources and opportunities, allowing them to capture more value. This phenomenon, common in scale-free networks, is represented by a power-law distribution :

Where k is the number of connections and γ determines the distribution’s steepness. The more central an individual is in a social network, the more value they can extract from relationships, creating a natural asymmetry between those with more connections and those with fewer.

This asymmetry mirrors the philosophical concept of power, as discussed by Michel Foucault, where certain individuals or groups hold disproportionate influence over others due to their centrality in social or political structures. Power, like value creation, is not equally distributed, and those with more access to resources can perpetuate this imbalance.

In short :

- Human relationships, whether familial, romantic, or platonic, are another area where value creation is frequently asymmetric. Two individuals rarely invest equally in terms of emotional energy, time, or resources, leading to imbalances in the perceived and actual value each derives from the relationship.

- In many relationships, especially romantic ones, there is often an imbalance in who carries the emotional labor. Emotional labor refers to the invisible work that goes into managing emotions, resolving conflicts, and maintaining the emotional well-being of a relationship. Frequently, one partner may invest significantly more in this unseen but crucial form of value creation, leading to an unequal distribution of relational benefits. While one person benefits from the stability and emotional nurturing, the other may feel drained, contributing more than they receive.

- Power dynamics can also drive asymmetry in value creation in relationships. For example, in hierarchical relationships — like those between a mentor and mentee, or a parent and child — the individual with more authority or control often receives more value (respect, influence, decision-making power) while contributing less on a day-to-day basis. While such imbalances may be structural, they nevertheless create uneven dynamics, where one party shapes outcomes more significantly than the other.

- In transactional relationships, where both parties expect an equal exchange of value (e.g., business relationships, certain friendships), asymmetry often arises when one person provides more than they receive, whether in terms of time, effort, or resources. Conversely, in non-transactional relationships, one party may give unconditionally, without expecting anything in return. While this form of giving may seem selfless, it too can create asymmetry, as one party derives value from the act of giving, while the other benefits from the receiving end.

3. Asymmetry in Organizations : Power Laws, Pareto Principle, and Information Asymmetry

In organizations, asymmetry in value creation is the norm rather than the exception. The Pareto Principle, or 80/20 rule, suggests that in most organizations, 80% of the value is created by 20% of the people. This disproportionality is not just an anomaly but a feature of how complex systems work. Understanding these dynamics requires a combination of statistical analysis, power-law distributions, and concepts from information theory.

Pareto Distribution : The 80/20 Rule in Organizational Value

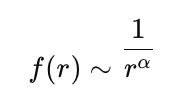

The Pareto Principle explains why value creation in organizations is rarely evenly distributed. In mathematical terms, the distribution of effort and reward follows a Pareto distribution, where a small number of employees, clients, or products generate the majority of the value :

Where xm represents the minimum possible value of the variable, and α is a constant determining the slope. In practical terms, a small number of employees or executives capture a disproportionate share of organizational rewards — salaries, recognition, or influence—while the majority contribute less to the overall value pool.

Power-Law Distributions : Leadership and Hierarchy

In hierarchical organizations, value creation is shaped by power-law distributions, where leadership captures more value simply by virtue of their position. This asymmetry in organizational structures can be modeled by Zipf’s Law, which describes how rank correlates with the frequency of value capture :

Where r is the rank and f® is the value captured. As one moves higher up in the hierarchy, the amount of value captured increases exponentially, creating an inherent imbalance where those at the top gain disproportionately from the efforts of those below.

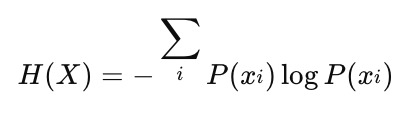

Information Asymmetry : Entropy and Knowledge Distribution

Value creation in organizations is also heavily influenced by information asymmetry, where leaders and decision-makers have access to more information than their subordinates. This asymmetry can be explained using Shannon entropy, which measures the uncertainty or randomness of information :

Those with more information reduce entropy and have a significant strategic advantage in decision-making, enabling them to create more value for themselves and the organization. Conversely, employees with limited information contribute less to the decision-making process, leading to a disproportionate capture of value by the few.

Philosophically, this aligns with the Marxist critique of capitalism, where those who control the means of production (or in this case, the flow of information) capture more value than the laborers who execute the organization’s day-to-day functions.

In short :

- Organizations, whether corporate entities or non-profit institutions, are driven by complex systems of value creation that are rarely, if ever, symmetric.

- In organizations, this principle highlights the inherent asymmetry of value creation: a small group of employees or departments often generate the majority of the value, while the rest contribute marginally.

- In many organizations, resources such as time, money, and talent are distributed unevenly, leading to asymmetries in value creation. Senior management may receive higher salaries and bonuses, not necessarily because they contribute more value than front-line workers, but because organizational structures prioritize and reward certain forms of value (decision-making, leadership) over others (execution, customer service). This can result in a skewed perception of value, where certain roles or positions are overvalued, while others are undervalued.

- Organizations are also shaped by knowledge asymmetry, where access to information, expertise, or strategic insights is not equally available to all employees. Those in leadership positions often possess a monopoly on critical information that allows them to make decisions and capture value more effectively, while lower-level employees, despite their skills and hard work, may not have the same access to value-creating opportunities.

- Asymmetry in value creation is especially visible in innovation and risk-taking within organizations. The organization as a whole may benefit from successful innovations, while the individual innovators may receive only a fraction of the value they have created, especially if the benefits are captured by shareholders or higher management.

Embracing Asymmetry : Navigating the Imbalances in Value Creation

The asymmetric nature of value creation is not inherently negative; it is simply a reality of how systems operate. Understanding these imbalances allows individuals and organizations to better navigate the complexities of value creation, and perhaps even leverage these asymmetries to their advantage.

Redefining Value : Rather than striving for perfect symmetry in every exchange, it may be more productive to recognize the multi-dimensional nature of value. Value can come in different forms — emotional, intellectual, material, social — and each form may be distributed differently across different parties. Accepting that value creation is often non-linear allows for more fluid, flexible relationships and organizational structures.

Mitigating the Negative Effects : To mitigate the negative effects of asymmetry, individuals and organizations can work towards more equitable systems of reward and recognition. This can include better distribution of resources, more transparent communication about expectations, and acknowledging invisible forms of value (like emotional labor or risk-taking).

Leveraging Asymmetry : Finally, those who understand the inherent asymmetries in value creation can use them to their advantage. By recognizing where value is disproportionately created or captured, individuals can position themselves strategically within relationships and organizations to maximize their own value creation potential.

Conclusion

Value creation is not, and likely never will be, perfectly symmetric. Value creation is inherently asymmetric, shaped by non-linear dynamics, power laws, and probabilistic events. Whether in life, relationships, or organizations, value is shaped by power dynamics, chance, resource distribution, and personal perspectives. Embracing this inherent asymmetry allows us to better understand the systems we operate in and helps us navigate the complex, often unequal exchanges that define our existence. In doing so, we can move beyond the illusion of perfect reciprocity and create more nuanced, meaningful forms of value for ourselves and others.

Thanks for dropping by !

Disclaimer : Everything written above, I owe to the great minds I’ve encountered and the voices I’ve heard along the way.