The Principal Agent Problem Across Life and Society

What happens when trust is delegated in a world driven by self-interest? Let's explore the principal-agent problem across life, corporate structures, and the economy, weaving philosophy, psychology, and existential reflection into an intricate tapestry of misaligned incentives...

The principal-agent problem, at its core, is about misaligned incentives — a dynamic that emerges when one party (the principal) delegates authority or responsibility to another (the agent). While this concept is firmly rooted in economic and organizational theory, its tendrils extend far beyond corporate boardrooms and financial markets. What does it mean for trust to be delegated in a world driven by self-interest? It’s a philosophical, psychological, and societal dilemma that shapes our choices, relationships, and even our sense of self.

When I first encountered the principal-agent problem, it seemed like an abstraction relegated to corporate governance and macroeconomic policy. Leaders versus shareholders, governments versus citizens, insurers versus policyholders. But as I delved deeper, I began to see it everywhere : in the way we make decisions about our health, our relationships, our careers, and even our existential priorities. In this essay, I’ll explore the principal-agent problem not merely as an economic phenomenon but as a lens through which we can understand life, living, and the intricate web of human behavior.

The Anatomy of the Problem

At its most basic, the principal-agent problem arises when :

- The principal entrusts the agent to act on their behalf.

- The agent’s goals diverge from those of the principal.

- Information asymmetry exists, allowing the agent to act in their own interest without immediate consequences.

Take, for example, a corporation. Shareholders (the principals) hire a leader (the agent) to maximize shareholder value. Yet, the leader might prioritize personal prestige, empire-building, or short-term profits over long-term growth. The shareholders’ ability to monitor and correct this behavior is constrained by the complexity of modern corporations, creating a gap ripe for exploitation.

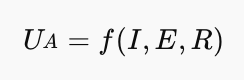

We can formalize this through a utility equation :

This highlights how the agent’s utility depends on a complex interplay of these factors, which must be carefully balanced to mitigate misalignment.

This dynamic is ubiquitous. In macroeconomics, central banks act as agents for the populace, managing monetary policy in ways that may not always align with public welfare. In microeconomics, an employee might prioritize minimizing effort over maximizing their contribution to the organization. Even within ourselves, we are often simultaneously the principal and the agent, torn between our long-term aspirations and short-term impulses.

The Principal-Agent Problem in Life and Living

Consider the human condition : we are creatures of contradiction, embodying multiple selves that often work at cross-purposes. Nietzsche’s concept of the Apollonian and Dionysian dualities speaks to this inner conflict — the disciplined, rational self striving for order against the impulsive, chaotic self drawn to immediate pleasures. As individuals, we delegate authority to our future selves, trusting them to make decisions that align with our long-term goals. Yet, our present selves frequently act as rogue agents, indulging in behaviors that undermine those aspirations. Freud’s notion of the id and superego adds another layer to this dynamic, where primal desires often clash with moral ideals, leaving the ego to mediate an uneasy truce.

- Health and Well-Being : Why do we procrastinate exercise, overindulge in unhealthy foods, or neglect sleep? Our long-term principal — the version of ourselves who values health and longevity — entrusts the present self to act accordingly. Yet, the present self, influenced by immediate gratification, often reneges on that trust. The agent betrays the principal.

- Relationships : In relationships, trust is the cornerstone of collaboration. Partners act as agents for each other’s emotional and physical well-being. When one partner’s actions prioritize self-interest over mutual benefit, the principal-agent problem rears its head, leading to conflicts and fractures.

- Existential Choices : Even our pursuit of meaning is riddled with principal-agent dynamics. We might prioritize careers that align with societal expectations (agent behavior) over those that fulfill our authentic desires (principal goals). This misalignment can lead to existential dissatisfaction.

The Corporate and Organizational Perspective

The corporate world offers fertile ground for observing the principal-agent problem in action. Can a corporation ever truly act in the best interest of its shareholders if its culture prioritizes profit over people? From the C-suite to entry-level employees, misaligned incentives and information asymmetries are endemic.

- Corporate Governance : Leaders, as agents, often prioritize short-term stock prices to secure bonuses, disregarding the long-term health of the company. Shareholders, dispersed and often poorly informed, struggle to enforce alignment.

- Team Dynamics : Within organizations, managers delegate tasks to employees, trusting them to act in the organization’s best interest. Yet, employees might optimize for personal convenience, creating inefficiencies and eroding trust.

- Decision-Making : Committees and boards — ostensibly designed to align diverse perspectives — often exacerbate the principal-agent problem. Group dynamics can dilute accountability, allowing individual agents to shirk responsibility under the guise of collective decision-making.

Mathematical Insights into Macro and Microeconomy

At both macro and micro levels, the principal-agent problem can be modeled mathematically to reveal the misalignment :

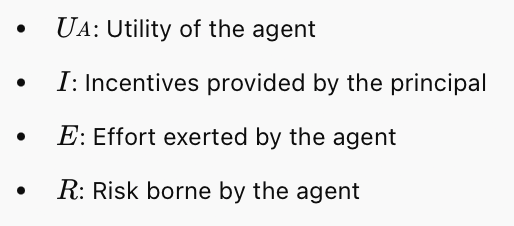

Information Asymmetry and Utility Gap

This gap quantifies the divergence between the principal’s and agent’s objectives. Understanding (\Delta U) can guide policies to minimize discrepancies through better monitoring or incentive structures.

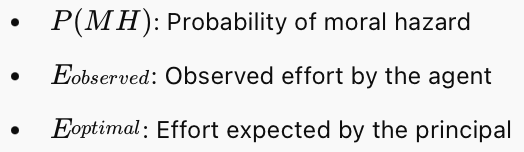

Risk of Moral Hazard

This equation captures the likelihood of agents acting against principals due to perceived low accountability.

Decision-Making and the Weight of Agency

Decision-making is inherently fraught with principal-agent tensions. Whether in organizations or personal life, our choices reflect a negotiation between competing priorities.

- Democratic Decision-Making : Democracies are predicated on the idea that elected representatives act as agents for their constituents. Yet, voter apathy and information asymmetry often allow representatives to prioritize special interests over public good.

- Authoritarian Decision-Making : In authoritarian regimes, the principal-agent problem is inverted. The leader assumes the role of principal, treating the populace as agents whose primary duty is obedience. This dynamic stifles accountability and perpetuates systemic inefficiencies.

- Personal Decisions : Even in our personal lives, decision-making is an interplay of principal-agent dynamics. Our future selves entrust our present selves to make choices that align with overarching goals. Yet, cognitive biases and emotional impulses often lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Resolving the Principal-Agent Problem

If the principal-agent problem is so pervasive, how do we navigate it? Solutions require a combination of structural reforms, incentive alignment, and self-awareness.

- Incentive Alignment : Whether in organizations, governments, or personal life, aligning incentives between principals and agents is paramount. This might involve performance-based compensation in corporate settings, or cultivating habits that align short-term actions with long-term goals in personal life.

- Transparency and Accountability : Reducing information asymmetry is critical. In organizations, this means fostering a culture of open communication and measurable outcomes. In governance, it requires robust institutions that hold agents accountable.

- Self-Reflection : On an individual level, resolving the internal principal-agent problem demands self-awareness. By understanding our cognitive biases and emotional triggers, we can make more deliberate choices that honor our long-term aspirations.

A Philosophical Perspective

Philosophically, the principal-agent problem invites questions about autonomy, trust, and authenticity. It also challenges us to consider the nature of trust itself : Is trust an act of calculated delegation, or does it embody a deeper, existential leap of faith? In this light, social contract theory becomes relevant, as it frames trust as the foundation of societal cohesion — a tacit agreement where individuals surrender certain freedoms to a collective agent in exchange for order and protection. Yet, modern ethics complicates this picture, questioning whether agents, be they individuals or institutions, can ever fully uphold the principles of trust without succumbing to self-interest. When we delegate authority — whether to another person, an institution, or even our future selves — we relinquish a degree of control. This act of trust is both empowering and perilous, reflecting the tension between individual agency and collective interdependence.

Existentialist thinkers like Sartre and Camus grappled with similar dilemmas, albeit in different contexts. Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom suggests that we are ultimately responsible for our choices, even when they’re mediated by agents. Camus’s exploration of absurdity underscores the inherent contradictions in human existence, including the dissonance between our aspirations (principals) and our actions (agents).

The Way Forward

The principal-agent problem, in its many forms, is a testament to the complexity of human behavior. It’s a reminder that misaligned incentives and information asymmetry are not merely economic phenomena but existential realities. By approaching this problem with intellectual rigor and philosophical depth, we can cultivate a more nuanced understanding of ourselves and our world.

In my own life, I’ve found that addressing the principal-agent problem begins with clarity of purpose. How often do we mistake clarity for certainty, and what risks does that pose to our long-term goals? When I’m attuned to my long-term goals and values, I’m better equipped to navigate the temptations and distractions that threaten to derail me. Whether it’s a corporate decision, a personal relationship, or a moment of existential reflection, the key lies in fostering alignment — between principal and agent, between aspiration and action, and ultimately, between self and self.

As we grapple with this pervasive dilemma, let us remember that the principal-agent problem is not merely something to be solved but a lens through which to explore the intricacies of human experience. It’s an invitation to reflect, to align, and to act — not as disparate agents, but as integrated principals of our own lives.

Thanks for dropping by !

Disclaimer : Everything written above, I owe to the great minds I've encountered and the voices I’ve heard along the way.