The Eternal Loop of Leverage in Finance

Every financial innovation — whether banks, derivatives, fintech, or DeFi — is just leverage repackaged. The core remains : amplifying returns by using more than one’s own capital. This essay unveils the eternal cycle of leverage, its risks, and its philosophical depth. Let's dive-in ...

I have long been fascinated by the way financial markets continuously morph and adapt, seemingly conjuring new products, instruments, and methodologies year after year. Yet, beneath the surface of these ever-evolving creations, I’ve come to realize that there lies a singular concept — one that shapes and reshapes the entire edifice of finance time and again. This concept is leverage. In one form or another, every financial innovation throughout history can be reduced to a reframing, repackaging, or reimagining of leverage. Whether it manifests in the establishment of ancient banks, the creation of complex derivatives, the emergence of decentralized finance (DeFi), or the ubiquity of buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) models, the essential ingredient remains : leveraging resources — be they capital, time, risk capacity, or information — to achieve outcomes greater than what one’s base capital alone would allow.

In one form or another, every financial innovation throughout history can be reduced to a reframing, repackaging, or reimagining of leverage.

In this essay, I want to travel through the annals of financial history and theory, demonstrating how leverage underpins each innovation, and then reflect on the future trajectory of this all-pervasive mechanism.

My Awakening to Leverage

The Elusive Core of Finance

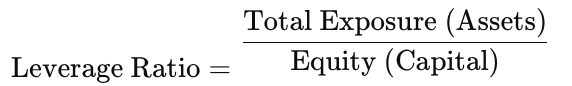

Early in my exploration of finance, I marveled at the breadth of instruments : equities, bonds, futures, options, swaps, structured notes, and so on. Each product appeared distinct, serving different investor profiles, risk appetites, and time horizons. But as I probed deeper, seeking the unifying principle, I discovered a deceptively simple formula :

This equation might seem rudimentary, but it encapsulates a nearly universal property of financial operations : we rarely restrict ourselves to using only the capital on hand. Instead, we borrow — or otherwise mobilize — additional resources to multiply our potential returns (while, of course, magnifying our risks).

The Philosophical Undercurrent

Philosophically, leverage stands at the intersection of ambition and limitation. It’s the embodiment of the human desire to do more with less. Archimedes, in a different context, famously said, “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.” In finance, leverage is the conceptual lever, and the fulcrum is the infrastructure — be it technological, legal, or institutional — that allows us to shift enormous financial weight with comparatively little capital. Thus, this concept carries not only mathematical clarity but also a profound reflection on human nature : our capacity for invention meets our inherent longing for growth, expansion, and at times, speculation.

Tracing Leverage Through History

Ancient Roots : Mesopotamia and Early Credit

My personal journey into historical finance started with the clay tablets of Mesopotamia, where some of the first recorded credit systems emerged around 2000 BCE. Temple communities and merchants granted loans of grain or precious metals, typically requiring repayment at harvest. The use of credit here was a straightforward form of leverage : farmers could sustain operations before the harvest, and merchants could purchase more goods than their immediate capital allowed.

These early credit systems already revealed the perpetual dynamic of leverage and risk. Whenever harvests failed or wars disrupted trade routes, debts could not be repaid — leading to social and economic turmoil. Even in this rudimentary form, leverage was both a source of economic dynamism and a harbinger of crisis.

The Medieval Renaissance and the Birth of Modern Banking

Moving forward in time, I observed how medieval Europe gradually birthed modern banking. The Italian city-states, particularly Florence and Venice, became incubators for innovative financial practices. The Medici family, for example, turned their banking enterprise into a powerhouse by accepting deposits and using those funds to make loans — again a classic leveraged arrangement. The ratio of deposits to the bank’s own capital was the fundamental metric of risk.

Yet, the beauty of the Medici model was in how they diversified and structured their loans — an early sophistication in leverage management. This not only propelled Renaissance commerce but also allowed for the financing of art, architecture, and vast trade expeditions. The core principle remained the same : using other people’s money (deposits) to extend more credit than one’s own capital base would permit.

The Rise of Stock Markets and Joint-Stock Companies

My exploration then took me to the 17th-century Dutch Republic, where the Dutch East India Company (VOC) exemplified a new kind of leverage. By issuing shares to a broad pool of investors, the VOC effectively multiplied the amount of money at its disposal for far-flung voyages and colonies. Shareholders provided capital, expecting dividends from the company’s overseas trade monopoly. This era also saw the advent of margin trading : the earliest speculators could borrow against existing shares to purchase more shares, intensifying both their upside potential and downside exposure.

The world’s first stock exchange, in Amsterdam, was thus born out of the friction between ambition (expanding trade routes to Asia) and limited individual capital. Collective investment, and the margin-based speculation that soon followed, created a potent new leverage-based system for wealth creation — and, inevitably, for risk accumulation.

Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries : Bonds, Derivatives, and Fractional Reserves

Fast-forwarding through the Industrial Revolution, I noticed leverage surfacing in diverse ways : corporate bonds to finance railways, municipal bonds to develop infrastructure, fractional reserve banking to enable a money multiplier effect. Each of these mechanisms expanded the effective capital base. For instance, fractional reserve banking multiplies the money supply by requiring banks to hold only a fraction of deposits as reserves. The rest can be lent out multiple times over.

In the early 20th century, the formalization of derivatives began with futures and options for commodities, eventually extending to financial assets. The 1973 Black-Scholes-Merton model gave mathematical rigor to option pricing, capturing the essence of leverage embedded in options contracts. The buyer of an option pays a small premium (capital outlay) for the right to control a larger amount of the underlying asset. Put simply, an option is a leveraged bet on the future price of a stock or commodity.

Each iteration, every new product — from convertible bonds to collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) — reveals a creative attempt to harness the power of leverage in a fresh way. The details change, the instruments become more mathematically complex, but the underlying impetus remains consistent : to amplify returns, often by transferring or dispersing risk in new, more efficient ways.

The Perpetual Cycle of Leverage and Crisis

Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis

The economist Hyman Minsky famously posited that financial systems tend to move from stability to instability as agents become more willing to take on leverage. In my own intellectual journey, encountering Minsky’s ideas gave me a powerful framework for understanding historical booms and busts — from the Tulip Mania of 17th-century Holland to the Great Depression, the dot-com bubble, and the 2008 financial crisis.

Leverage, in Minsky’s lens, progresses in three stages :

- Hedge Finance : Borrowers have enough cash flow to cover both interest and principal.

- Speculative Finance : Borrowers can cover interest but need to roll over principal.

- Ponzi Finance : Borrowers can neither pay principal nor interest out of current cash flow; they rely on asset appreciation or refinancing to stay afloat.

I find Minsky’s hypothesis particularly compelling because it underscores an eternal truth : leverage, if not carefully managed, sets the stage for self-amplifying cycles of expansion and contraction. When asset values keep rising, more borrowing seems justified. But as soon as a shock occurs, the reverse feedback loop kicks in — margin calls, forced selling, and a systemic credit crunch.

Quantifying the Leverage Risk

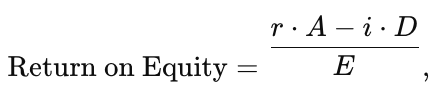

Financial mathematics offers a structured way to analyze risk. Consider a simple model where an investor’s equity (E) is used as partial collateral to borrow (D) dollars, for a total investment of (A = E + D). If the returns on (A) are (r), then the investor’s equity return is :

where, (i) is the interest rate on the debt. As (D) grows relative to (E), the variability in the investor’s equity returns increases. In other words, the “equity slice” must absorb not only the normal market fluctuations but also the additional volatility introduced by the debt service. This simple formula captures the essential risk magnification that has repeated in countless guises throughout financial history.

Modern Finance : Still the Same Leverage Story

Fintech : A Technological Wrapping of Leverage

In the last decade, I’ve watched the fintech explosion with keen interest. Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms, such as LendingClub and Prosper, brought a new wave of excitement by matching individual borrowers and lenders through user-friendly digital interfaces. Yet behind the scenes, these platforms still function via leverage. They pool capital from multiple lenders, disbursing loans that can exceed any single participant’s capacity.

Similarly, the buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) phenomenon, championed by companies like Klarna, Afterpay, and Affirm, is effectively short-term consumer credit. It allows consumers to purchase goods immediately while deferring payment — again a classic example of leveraging future income or future capital availability. The technology might be novel, the user experience more seamless, but the fundamental principle is the reallocation of buying power from a future state to the present.

Algorithmic Trading and High-Frequency Trading (HFT)

Technological sophistication has also birthed new forms of leverage in markets — most notably algorithmic and high-frequency trading. Firms employ sophisticated algorithms and colocation servers to trade in nanoseconds, exploiting minuscule price discrepancies. But how do these firms multiply returns? They often leverage large sums of borrowed capital on very short timeframes, turning fleeting arbitrage opportunities into substantial profits. Again, it’s a repackaging of leverage — this time supercharged by speed and computational power.

DeFi : Decentralized Leverage

When I encountered decentralized finance (DeFi), I initially viewed it as a radical break from traditional finance. However, as I spent more time analyzing smart contracts on platforms like Ethereum, I saw the same leverage patterns reemerge in a new context. Protocols like Aave, Compound, and MakerDAO allow users to deposit crypto assets as collateral, mint stablecoins, or borrow tokens for yield farming. The conversation around “overcollateralization” simply translates to the typical margin calls we see in centralized finance, albeit automated through smart contracts.

One can enter a liquidity pool by providing tokens that are then used by others for trading (leveraged trades included). The liquidity provider earns fees but also shoulders “impermanent loss,” a fancy term for potential market risk. So again, DeFi’s novelty lies in its decentralized, permissionless architecture — not in its escape from the gravitational pull of leverage. If anything, DeFi intensifies the leverage cycle by automating it, making it more accessible, and removing traditional gatekeepers.

Philosophical Dimensions of Leverage

Human Desire and the Illusion of Control

Through my study, I’ve often asked : Why is leverage so fundamental to finance? On one level, it satisfies our drive for growth, expansion, and immediate gratification. It allows humans to project themselves into a future where returns are higher, or resources more abundant. This resonates with our inherent optimism, or conversely, our anxiety about scarcity, pushing us to maximize what we have.

Yet, leverage also plays to the illusion of control : the belief that we can harness risk, contain it within formulas, and fine-tune it to produce consistent results. The history of finance suggests that while we can do this successfully for long periods, black swan events — or simply the unforeseen — eventually expose the fragility inherent in leveraged systems. Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s notion of “black swans” highlights that leverage often magnifies the impact of rare, unexpected events.

Societal and Ethical Reflections

On a broader societal level, leverage reflects the distribution of power and opportunity. In many systems, only certain institutions or individuals can access the best leverage opportunities, a phenomenon that underpins conversations about inequality. A large-scale investor might borrow at a few percentage points, while a subprime borrower faces double-digit interest. This discrepancy stems from perceived credit risk, but it also feeds into a cycle where those with access to cheap leverage can multiply their capital quickly, further distancing themselves from those without.

Risk Management and the Eternal Quest for Stability

The Role of Regulation

Governments and regulators have historically oscillated between promoting leverage (to stimulate growth) and restricting it (to prevent crises). The Basel Accords for banks, for instance, set minimum capital requirements, effectively capping the leverage ratio. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, new regulations like Dodd-Frank in the U.S. sought to curtail the riskiest forms of leverage by mandating higher capital buffers, imposing the Volcker Rule (limiting proprietary trading), and demanding transparency in derivatives markets.

Yet, as I observed, regulation often lags behind financial innovation. By the time rules are updated, the market has already found new instruments — like synthetic collateralized obligations, or complex exchange-traded notes — to circumvent or exploit loopholes. The push-and-pull between innovation and regulation is itself a testament to how central leverage is. It drives growth but also necessitates oversight.

Quantitative Tools for Monitoring Leverage

One of my personal interests is in the quantitative tools used to measure and manage leverage. Metrics like Value at Risk (VaR), Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), and stress testing aim to capture the potential losses under various scenarios. While these tools can be highly sophisticated, they often rely on historical data and assumptions about correlations that might not hold in turbulent times.

Consider a hypothetical bank that holds a portfolio of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The bank might assess its VaR based on historical default rates, only to be blindsided if the real estate market collapses in a way that defies past patterns. In that sense, risk management frameworks remain partially blind to the future, especially under conditions where leverage amplifies feedback loops and correlations between assets shift dramatically.

The Future of Financial Innovation : Repackaging Leverage Yet Again

AI-Driven Finance

I foresee artificial intelligence further embedding leverage into the financial landscape. Machine learning algorithms will quickly identify optimal capital structures or discover fleeting market inefficiencies that can be exploited using high degrees of leverage. Robo-advisors already suggest portfolios to retail investors, but with more advanced AI, we might witness a hyper-personalized leverage model : real-time adjustments in margin levels, continuous re-hedging, and algorithmic optimization of borrowing costs.

This might usher in a more stable system if the AI properly accounts for tail risks, or it could accelerate systemic fragility if the same algorithms converge on similar strategies and then unwind simultaneously during panics.

Quantum Finance

While still in a nascent stage, quantum computing has been touted as the next major leap in computational power. Some researchers believe it could revolutionize portfolio optimization, cryptography, and risk analysis. However, even if quantum algorithms provide sharper valuations and hedging strategies, the underlying impetus — amplifying returns via leveraged positions — will remain. The newfound computational capabilities will likely lead to new forms of derivative contracts and risk transfer mechanisms, but the cyclical pattern of leverage expansion and contraction is unlikely to disappear.

Sustainable Leverage?

In my moments of optimism, I ponder whether there is a “sustainable leverage” model — one that fosters economic growth without the drastic boom-bust cycles. Initiatives like impact investing and green bonds suggest that finance can be aligned with positive social and environmental outcomes. Could there be a future where the structuring of leverage explicitly accounts for externalities, ensuring that borrowed funds are channeled into productive, sustainable projects? Perhaps. But human history suggests that speculation and the desire for immediate gain often override these higher ideals, at least without strong institutional frameworks.

Conclusion : My Personal Reckoning with Leverage

After wandering through the annals of financial history, analyzing mathematical models, and grappling with philosophical questions, I have become convinced that leverage is the eternal loop of finance. Each epoch’s “new” product — whether it’s a Medici loan contract, a 17th-century stock certificate, a 20th-century derivative, or a 21st-century DeFi protocol — ultimately revolves around the same principle : amplifying economic potential by using more resources than one currently possesses.

The differences lie in who gets access to leverage, how risk is repackaged, and what tools are used to measure, manage, or hide it. This cyclical dance continues because it resonates with fundamental aspects of human ambition, ingenuity, and sometimes, folly. We harness leverage to accelerate growth, to innovate our way out of constraints, and to fulfill the age-old dream of building a future that surpasses our present means. But this same mechanism can overwhelm us when poorly managed, sowing the seeds of crisis.

I find a paradoxical beauty here. Leverage, in its broadest sense, is a testament to humanity’s creative capacity — we take something finite and transform it into something seemingly infinite. Yet, that illusion of infinity eventually confronts the hard boundaries of reality, reminding us of the delicate interplay between potential and risk.

If there is a lesson I carry forward, it is the need for humility and vigilance in the face of leveraged systems. The moment we become too certain of our risk models, too confident that we have tamed volatility, is likely the moment we set the stage for the next reckoning. In embracing leverage as the engine of financial and economic progress, we must also accept that it can be the architect of collapse. Balancing these dualities is the timeless challenge of finance — and perhaps a challenge that mirrors the broader human condition.

In closing, let me restate the central theme I’ve come to embrace : every financial innovation is just leverage dressed in new clothes. Whether we build next-generation AI-driven hedge funds, expand microfinance in developing nations, or deploy code-based smart contracts to handle billions of dollars in digital assets, the essential structure remains. Leverage is both the question and the answer, the puzzle and the key, repeatedly guiding the course of financial history and shaping the trajectory of our collective future.

And so, the eternal loop continues, with each revolution revealing new possibilities and perils. My hope is that by recognizing and understanding this fundamental truth — by gazing unflinchingly at the essence of leverage — we can participate in the ongoing evolution of finance more wisely, employing its immense power for genuine progress while vigilantly guarding against its inevitable risks. It is a delicate balance, one that will demand our keenest intellect, our most thoughtful ethics, and our deepest humility. Yet, for those of us captivated by finance, it is also a journey of perpetual fascination — a journey that never truly ends.

Thanks for dropping by !

Disclaimer : Everything written above, I owe to the great minds I've encountered and the voices I’ve heard along the way.